Introduction

In recent years, social media, particularly social networking sites like Facebook, have grown in popularity and usage [1]. Almost a billion people use Facebook globally [2]. Thus, indeed social networking sites enable users to build electronic personas, share information about their lives and experiences, upload photos, maintain relationships, organize social gatherings, meet new people, comment on other people's lives, express their beliefs, preferences, and emotions, and satisfy their need to belong [3]. Eventually, Facebook environment offers users an extra chance to post on their profile more detailed information about themselves, as well as to post messages, photos/videos and/or web links on their online friends’ “walls”. These features, combined with the possibility of creating groups chatting, applications and fan pages make Facebook platform where mutual social interaction is significantly enhanced in various ways [4]. With its usability across countries the internet and other electronic gadgets have given teenagers new socialization opportunities, however they have also made it possible for new types of harmful interactions, such as cyberbullying [5].

Most studies on cyberbullying and self-esteem focused only the impact of self-esteem on the cybervictim where victims of cyberbullying tend to have lower self-esteem than those who have no experience [6]. Other studies also focus on gender differences, racial differences, and the reason behind the cyberbullying behaviors [7]. On the other hand, although most research claims that the cybervictims are most likely to have lower self-esteem, however, in another research on bullying perpetration and victimization, it emphasizes the role bullying plays in social dominance, bullies' inflated self-views, and the repercussions of bullies' actions on victims wherein bullies were affected by the behaviors of their victims- a possibility of cybervictims and cyber aggressors to have low self-esteem [8]. Bullies showed lower school performance-related but higher social self-esteem. Both bullies and victims showed lower school adjustment and more loneliness [9].

Hearing the word cyberbullying encounter, it will always trace back to the cyber victimization and yet so often to take side the cyberbullies themselves [10]. Most studies focus on different sides of cyberbullying and its factors affecting the lower self-esteem of the victim which include gender differences, racial differences and etc. Only they focus on healing and providing of intervention after getting the results of their study to the cybervictims alone but rarely in preventing cases to happen (the side of the cyberbullies) [11]. Nonetheless, this study will open a way to hear the side of the cyberbullies by determining the cyberbullying experiences of both cybervictim and cyberbully [12]. The objective of this study is to determine how frequent the cybervictim were bullied and how frequent the cyberbully engaged in cyberbullying and its effect to the level of self-esteem in the six dimensions of self-esteem such as the social, competence, affect, academic, family, and physical dimension [13]. Frequency of cyberbullying experiences and level of self-esteem in six dimensions will be quantified in this study [14].

Materials and Methods

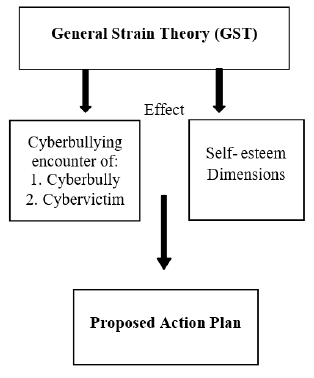

This study is anchored on Robert Agnew’s General Strain Theory (GST) which explained the understanding motivation behind cyberbullies and that is the gap between feelings of aspirations and expectations [15]. In the 1930’s, Merton stated that those people who felt the pressure of success but did not reach their expectations they were most likely to engage in deviant behaviors in order to help themselves reach their aspirations [16]. Moreover, GST suggests that as individuals are pressured and pushed up against the wall, this will eventually result in a negative feeling and ultimately towards deviant or risky behaviors [17]. Another specification of GST on the relevant offending which include the high magnitude (severe, frequent, of long duration, or involving matters of high importance to the individual), are seen as unjust and associated with low social control and will eventually lead to deviant or negative behaviors [18]. The result of these deviant behaviors includes being the victim of cyberbullying or cyberbullying victimization [19]. On the other hand, GST also claimed that deviant behaviors like cyberbullying are responses of multiple factors; “The choice of coping strategy such as crime is likely influenced by the convergence of several factors, including the characters of the individual, the character of the stressor, and the circumstances surrounding the stressor”.

In the context of the internet and social media like Facebook, individuals that are less popular, or are bullied at school because of a power imbalance, could turn to cyberbullying as a means of coping or seeking revenge [20]. Agnew broadened the definition of strain theory to include “events or conditions that are disliked by individuals” including on social media. Under the broad definition of GST includes three major parts of factors (strains). The first major type is the inability of individuals to achieve their goals a dysfunction between aspirations and expectations. The second major type is the presentation of noxious or negatively valued stimuli. This applies to those people who experience undesirable circumstances or in the recipient of negative treatment in others, such as harassment and bullying and cyberbullying. The third major type is the loss of positively valued stimuli. This involves the loss of something valued and encompasses a wide range of undesirable events or experiences. The second major type emphasizes the connection to the study on cyberbullying experiences on both the cyberbully and cybervictim. Those who were cyberbullied on frequent basis is expected to have a relatively strong relationship to negative behaviors. This experience shows a highly noxious and is likely to generate anger and desires for revenge. Thus the cybervictim of the cyberbullying may believe that striking back will help end or alleviate the strain.

Olweus claimed that a bully had to have some physical dominance or more power imbalance over their victim(s). Unlike traditional bullies, cyberbullies today can be of any size and age and through anonymous accounts, can remove that necessary power feature to be stronger or physically more dominant. A study of Timothy Oblad with the integration of GST found among cyberbullies that they often report higher psychosocial challenges depressions and problematic behaviors. In addition, Sabella et al., cited that cyberbullies tend to be motivated by revenge seeking behaviors yet in reality they have lower self-esteem but tend to engaged in cyberbullying as their coping and/or defense mechanism.

This theory will help support the objectives of the study on the effect of cyberbullying in both the cyberbully and cybervictim to the six dimensions of self-esteem. GST will also help expound the claim of the study and will provide support to the following variables being utilized for better discussions to whatever will be the results of this study (Figure 1).

The GST helps to explain the behavior and experiences of both the cyberbully and cybervictim. The GST to cyberbullies behaviors claimed that they tend to behave negatively through experiences. They are most likely called cybervictim-bully. Those who have increasingly deviant experiences were more likely to engage in cyberbullying. Factors affecting behaviors include negative emotions (e.g., anger, frustration, revenge, etc.) serve as the vehicle to push this youth to turn to perpetration. Social dominance theory expounds the idea that because of the wide range of social media, most likely Facebook for anyone can create accounts and use the platform. With that anyone can also be cyberbullies and cybervictim without even knowing each other but with the intentions to inflict feelings of hurtfulness, fear, or helplessness, in other word to harass someone and force them into submission. Cyberbullies cannot see target’s immediate reaction, they will even be more aggressive and callous to ensure harm to the victim, ultimately, ensuring superiority over the victim. Those who are cybervictim bully will most likely to engage in negative coping methods that may lead to deviant behaviors or potentially self-harm. Cybervictim responses, on the other hand, upon realizing they are being cyber attacked, some would not allow attackers to see or sense of reactions, ignoring them, that will inhibit a fear and sadness among cybervictims and were positively related to self-harm or will have lower self-esteem and even thoughts about suicide. Negative emotions are connected to feelings of negativity resulted from having a high level of self-control removed any harmful effect from cyberbullying. The cyberbully and cybervictim, as explained in GST, haves past experiences that trigger and pushed them to act as the perpetrator and victim. Both cyberbully and cybervictim have negative thoughts and behaviors that led them to have lower self- esteem in reality. However, unlike cybervictims the cyberbullies tend to be aggressive and revengeful online but not offline for they are more likely victims. Cyber victims on the other hand, have lower self-esteem like sadness, loneliness, anxiety and even will led them to self-harm and even the worst to suicide. As this study aims to determine the effect of both the perpetrators and cybervictims encounters on cyberbullying, this study will be of great help to those people who can benefit the study. Cyberbullying nowadays has been rampant due to the different social media platforms. Many people still have no idea that they were cyberbullied already and same goes with the cyberbully, they might not know that they have bullied someone already. As defined by Yasin N Silva et al., that cyberbullying encompasses sense of domination and counteract the threat. However, at-risk youth have difficult time ignoring directly harmful messages and could be at a greater risk for becoming dominated by a cyberbully which could lead to misguided decisions.

On the other hand, the GST to cybervictim behaviors also claimed that cyberbullying led to elevated level of fear and sadness among cybervictims and were positively related to self-harm or will have lower self-esteem and even thoughts about suicide. Negative emotions are connected to feelings of negativity resulted from having a high level of self-control removed any harmful effect from cyberbullying. The cyberbully and cybervictim, as explained in GST, haves past experiences that trigger and pushed them to act as the perpetrator and victim. Both cyberbully and cybervictim have negative thoughts and behaviors that led them to have lower self- esteem in reality. However, unlike cybervictims the cyberbullies tend to be aggressive and revengeful online but not offline for they are more likely victims. Cyber victims on the other hand, have lower self-esteem like sadness, loneliness, anxiety and even will led them to self-harm and even the worst to suicide.

As this study aims to determine the effect of both the perpetrators and cybervictims encounters on cyberbullying, this study will be of great help to those people who can benefit the study. Cyberbullying nowadays has been rampant due to the different social media platforms. Many people still have no idea that they were cyberbullied already and same goes with the cyberbully, they might not know that they have bullied someone already. As defined by Yasin N Silva et al., that cyberbullying encompasses spreading false or embarrassing data about someone through digital media and it causes and manifests low self-esteem, this issue and/or deviant behavior occurred in social media can affect the physical, emotional/affect, competence, family, and social dimensions of the cybervictim or even to the ones starting the cyberbullying for a myriad of reasons. Cyberbullying will not occur without the involvement of both the perpetrators and the cybervictims and so both are the priorities for the aims of the study.

Methods

The researchers in this study will utilize the quantitative research design. Specifically, the descriptive approach will be used. The descriptive approach is utilized to describe the Facebook as a medium of cyberbullying cases of the study. The measure as to how frequent the cybervictim were bullied and how frequent the cyberbully engaged in cyberbullying and its effect to the level of self-esteem in the six dimensions of self-esteem such as the social, competence, affect, academic, family, and physical dimension will be quantified. Frequency of cyberbullying experiences on both the cyberbully and cybervictim and level of self-esteem in six dimensions will be measured in this study. This study will also apply a purposive sampling assuming the respondents whether or not they engaged in cyberbullying and whether or not they were victims of cyberbullying.

Results and Discussions

Table 1 shows the distribution of the cyberbullying encounter on Facebook. The results showed that among 100 respondents, 14 are cybervictim-bully, 21 are cybervictim with a total of 35 cybervictims, and 65 are neither cybervictims nor cyberbullies.

| Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

Total |

| Yes |

No |

| Yes |

14 |

0 |

14 |

| No |

21 |

65 |

86 |

| Total |

35 |

65 |

100 |

Table 1. The cyberbullying encounter of the cyberbully and cybervictim on Facebook.

Cyberbullies, as outlined by Agnew, typically display negative behaviors stemming from past experiences, with a higher prevalence of cyberbullying among those with progressively deviant encounters. Negative emotions such as rage and frustration serve as triggers for involvement in cyberbullying. The social dominance theory suggests that the diverse nature of social media enables anyone to become a cyberbully or cybervictim, irrespective of acquaintance, as long as they share the goal of emotionally harassing someone. Emphasized by Sabella et al., cyberbullies are often motivated by revenge-seeking behaviors, coupled with lower self esteem, using cyberbullying as a coping or defense mechanism.

In the study, only 35 out of 100 respondents were included in the analysis, as the measurement focused on a specific population within the total respondents. Of these, 14 individuals were both cybervictims and bullies, while 21 were cybervictims alone. The use of purposive sampling, guided by the minimum acceptable sample size of at least 30 according to Fraenkel and Wallen, was considered, emphasizing that data from smaller samples may not adequately reflect the phenomenon being measured.

The predominant pattern among the respondents was identified as cybervictim-bully, aligning with the cycle of victimization theory, which suggests that those who have experienced bullying, including cyberbullying, may become bullies themselves in an attempt to regain lost power or status. Some studies propose that individuals subjected to cyberbullying may resort to such behavior as a coping mechanism for the negative emotions associated with victimization, seeking revenge to regain control or power. Psychological impacts of cybervictimization, as well as aggressive tendencies developed in response to emotional distress, are highlighted in other studies. Moreover, individuals with low self-esteem, having been victims of cyberbullying, might engage in such behavior to boost their self-esteem or retaliate against perceived threats, aligning with the results obtained from the respondents.

Table 2 displays data on the frequency of cyberbullying encounters on Facebook, encompassing activities like posting embarrassing pictures, leaving harsh comments, using someone's account, spreading rumors, using someone's identity, sending explicit content, exposing private conversations, sending demanding messages, and editing photos offensively. The findings reveal that these cyberbullying activities are generally infrequent, with mean scores ranging from 2.00 to 2.79. Standard deviations provide additional insights into response variability. Remarkably, the occasional use of classmates' inappropriate images as memes for amusement scored higher in frequency compared to other cyberbullying behaviors.

| Statements |

Cyberbully |

| Average and SD |

Interpretation |

| I post pictures (odd) of my classmates to mock/embarrass them. |

2.21 (0.80) |

Rare |

| I leave harsh/foul comments on someone's post. |

2.36 (0.84) |

Rare |

| I use someone's account and post embarrassing pictures on it. |

2.21 (1.12) |

Rare |

| I spread rumors about someone online for my personal gain. |

2.36 (1.22) |

Rare |

| I use someone's identity online for my personal gain. |

2.43 (1.16) |

Rare |

| I send pornographic/obscene images or messages (e.g. photographs of cartoons or nude people or animals engaging in sexual acts) to someone. |

2.43 (1.22) |

Rare |

| I exposed private and anxious conversation of my classmates/friends to others without their consent |

2.00 (0.96) |

Rare |

| I send excessively "needy" or demanding measures (i.e., pressuring to see you, assertively requesting you to go out on a date, arguing with you to give him/her or other chances etc.). |

2.21 (0.97) |

Rare |

| I edit photos in offensive manner on the internet. |

2.21 (1.05) |

Rare |

| I use my classmate's inappropriate images as memes to make fun of them |

2.79 (0.89) |

Sometimes |

| Note: 1.00-1.74: Never, 1.75-2.49: Rare, 2.50-3.24: Sometimes, 3.25-4.00: Always |

Table 2. Cyberbullying encounter of the cyberbully on Facebook.

Savoldi and Ferraz de Abreu found that cyberbullying behaviors are influenced by factors such as users' online hours, frequency of activity, and usage of various online mediums. Heavy internet users, engaging in at least 10 activities per person, were more likely to bully and be victimized online, with a notable focus on social networking sites like Facebook. The frequency of cyberbullying encounters was linked to the daily usage of these heavy internet users. Additionally, excessive Facebook usage is associated with depression and decreased well-being, impacting individuals' self-esteem.

The results indicate that the majority of college students in the college of arts and sciences at Cebu Technological University, who have encountered cyberbullying, are not heavy internet users. The current societal landscape is different, with social media platforms responding rapidly to cyberbullying cases due to increased societal demand for human rights and moral attention. Statistics reveal a decline in cyberbullying cases, attributed to the strict policies on offensive content and inappropriate images implemented by social media platforms. Notably, platforms like Facebook have strengthened their reporting policies to combat fraud and cyberbullying.

While a consistent association exists between victimization and lower self-esteem, the connection between cyberbullying perpetration and lower self esteem shows some inconsistency. Studies on traditional bullying among adolescents have produced diverse outcomes. Some authors posit that victims of cyberbullying may be more susceptible to experiencing low self-esteem, thereby negatively affecting their psychological development, overall well-being, and daily routine.

Table 3 displays data on cyberbullying encounters of cybervictims on Facebook, revealing that such incidents are generally rare. The encounters include being mocked online for physical appearance, character, or experiences, receiving threats or harsh messages, encountering incorrect and mean-spirited information, exclusion from online groups, personal information misuse, receiving sexually allusive proposals, unauthorized sharing of personal photos and videos, facing software attempting to obtain personal information, receiving harsh jokes on posts, and having photos stolen and posted online for mockery. The mean scores range from 2.14 to 2.46, with standard deviations providing additional insights into the variability of responses. Overall, the findings suggest a limited frequency of cyberbullying encounters for cybervictims on Facebook.

| Statements |

Cybervictim |

Average

and SD |

Interpretation |

| Being mocked in online social utilities because of my physical appearance, my character, or an instance I experience. |

2.34 (0.88) |

Rare |

| Receive threatening or harassing messages. |

2.20 (0.84) |

Rare |

| Seeing incorrect and mean-spirited things written about me. |

2.14 (0.74) |

Rare |

| Being specifically and intentionally excluded from an online group/chatroom. |

2.31 (0.94) |

Rare |

| Facing with people using my personal information without my consent. |

2.20 (0.87) |

Rare |

| Receiving proposals with sexual allusions from people I know/I don't know. |

2.37 (0.92) |

Rare |

| Publication of my personal photographs and videos without my consent |

2.43 (0.89) |

Rare |

| Suffering from software aiming to get my personal information |

2.29 (0.88) |

Rare |

| Receiving harsh jokes on my posts. |

2.46 (0.89) |

Rare |

| Someone stole photos of me and posted them on social media to make fun of me. |

2.43 (0.96) |

Rare |

| Note: 1.00-1.74: Never , 1.75-2.49: Rare, 2.50-3.24: Sometimes, 3.25-4.00: Always |

Table 3. Cyberbullying encounter of the cybervictim on Facebook.

The data, supported by studies like Dredge et al., and Baron et al., reveals that cyberbullying victimization on Facebook is generally rare. Dredge et al., found a strong correlation between Facebook characteristics, traditional bullying experiences, and a higher likelihood of cyberbullying victimization, with predictors including the number of Facebook friends and traditional bullying incidents. This emphasizes the importance of educational programs to prevent cyberbullying and inform teenagers about reducing vulnerability on social media platforms. Additionally, Baron et al., reported that 55% of college students had been cybervictims, mostly experiencing it rarely, attributed to more developed platforms like Facebook with robust cyberbullying policies. The swift response of platforms like Facebook to inappropriate content contributes to the rarity of cyberbullying incidents. Overall, this collective evidence highlights the cause and effect relationship between victimization and social media, underscoring the need for preventative measures and experimental evidence in understanding these dynamics.

Table 4 displays the social self-esteem of students categorized as cyberbullies or cybervictims. Cyberbullies exhibit high self-esteem, as evidenced by their comfort in communicating with others who share similar interests (mean: 3.71, standard deviation: 0.47), their lack of concern for others' impressions in decision-making (mean: 4.07, standard deviation: 0.47), and their preference for socializing with positively minded individuals (mean: 3.43, standard deviation: 0.65). They also show moderate self-esteem, being not afraid to misunderstand others' decisions thoroughly (mean: 3.93, standard deviation: 0.47) and finding it easy to socialize in small groups (mean: 3.36, standard deviation: 0.63). Additionally, cyberbullies possess the ability to make people comfortable even in the first approach with shared interests (mean: 2.57, standard deviation: 0.76), indicating high self-esteem in social interactions.

| Social dimension |

Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

| Average and SD |

Interpretation |

Average and SD |

Interpretation |

| I am comfortable communicating to others with the same interest of mine. |

3.71 (0.47) |

High

self-esteem |

3.71 (0.46) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I am not concerned with the impression of others in the decision I am making. |

4.07 (0.47) |

High

self-esteem |

4.17 (0.62) |

High

self-esteem |

| I like to socialize with others who have positive outlooks in life. |

3.43 (0.65) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.51 (0.56) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I am not afraid that I may not understand the decision of others as thorough as I'd like |

3.93 (0.47) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.83 (0.57) |

High

self-esteem |

| I can easily make people comfortable even in the first approach with me. |

2.57 (0.76) |

High

self-esteem |

2.77 (0.65) |

High

self-esteem |

| I find it easy to socialize in a small group of people. |

3.36 (0.63) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.23 (0.69) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| Note: 1.00-2.49: Low self-esteem, 2.50-3.24: Moderate self-esteem, 3.25-4.00: High self-esteem |

Table 4. Social self-esteem of students according to their role as a cyberbully or a cybervictim.

In contrast, cybervictims display a range of social self esteem traits. They are moderately comfortable communicating with others who share the same interest (mean: 3.71, standard deviation: 0.46). They exhibit high self-esteem in decision-making, being unconcerned with others' impressions when making decisions with shared interests (mean: 4.17, standard deviation: 0.62). Cybervictims also show moderate self-esteem, expressing a preference for socializing with positively minded individuals with shared interests (mean: 3.51, standard deviation: 0.56). They are not afraid to not thoroughly understand others' decisions (mean: 3.83, standard deviation: 0.57), indicating high self-esteem. Furthermore, cybervictims find it moderately easy to socialize in small groups (mean: 2.77, standard deviation: 0.65) and easily make people comfortable in the first approach with shared interests (mean: 3.23, standard deviation: 0.69), reflecting a mix of moderate and high self-esteem in various social scenarios.

Self-esteem, as highlighted by Mann, Hosman, Schaalma, and de Vries, significantly influences one's thoughts and perception of the world. Despite the challenges posed by cyberbullying encounters, individuals do not thrive in isolation; socialization is crucial for effective functioning. Maintaining social engagement is emphasized as essential, with interpersonal trust as a key factor. Interpersonal trust is defined as the willingness to be vulnerable based on the expectation that others will act in a particular way, facilitating smoother social functioning.

Table 5 presents the competence self-esteem of students categorized as cyberbullies. cyberbullies exhibit high self-esteem as they confidently showcase their skills without fear of judgment (mean: 3.79, standard deviation: 0.8). They feel a sense of happiness when their efforts are appreciated (mean: 3.64, standard deviation: 0.63) and are encouraged to contribute their abilities when others rely on them (mean: 3.29, standard deviation: 0.61). Additionally, they do not feel disappointed when tasks are not done properly (mean: 4.36, standard deviation: 0.5). However, in certain aspects, they show moderate self-esteem, being confident in their abilities (mean: 2.86, standard deviation: 0.53) and not easily giving up when faced with criticism (mean: 3.36, standard deviation: 0.63).

| Competence dimension |

Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

Average

and SD |

Interpretation |

Average and SD |

Interpretation |

| I am always confident in my abilities |

2.86 (0.53) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

2.77 (0.73) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I do not doubt showing my skills to others for I am afraid to be judged. |

3.79 (0.8) |

High

self-esteem |

3.74 (0.74) |

High

self-esteem |

| I feel happy when someone appreciates my efforts and abilities. |

3.64 (0.63) |

High

self-esteem |

3.66 (0.59) |

High

self-esteem |

| I do not give up easily when someone criticizes my efforts. |

3.21 (0.97) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.37 (0.91) |

High

self-esteem |

| I feel encouraged to contribute my abilities when I feel someone is relying on me. |

3.29 (0.61) |

High

self-esteem |

3.26 (0.61) |

High

self-esteem |

| I do not feel disappointed when I don't do my task properly. |

4.36 (0.5) |

High

self-esteem |

4.31 (0.47) |

High

self-esteem |

| Note: 1.00-2.49: Low self-esteem, 2.50-3.24: Moderate self-esteem, 3.25-4.00: High self-esteem |

Table 5. Competence self-esteem of students according to their role as a cyberbully or a cybervictim.

Table 5 illustrates the competence self-esteem of students categorized as cybervictims. Cybervictims display high self-esteem in various aspects, as they confidently showcase their skills without fear of judgment (mean: 3.74, standard deviation: 0.74). They experience happiness when their efforts are appreciated (mean: 3.66, standard deviation: 0.59) and demonstrate resilience by not giving up easily when faced with criticism (mean: 3.37, standard deviation: 0.91). Moreover, they feel encouraged to contribute their abilities when someone relies on them (mean: 3.26, standard deviation: 0.61) and do not feel disappointed when tasks are not done properly (mean: 4.31, standard deviation: 0.47). Additionally, they maintain confidence in their abilities (mean: 2.77, standard deviation: 0.73), reflecting a positive self-esteem in their competence.

This dimension aims to illustrate how a person's skill level is influenced by their self-esteem, considering their experiences as both a cyberbully and a cybervictim. The results indicate that individuals, regardless of whether they are a cyberbully or cybervictim, effectively manage daily tasks in diverse settings, such as work, school, and other environments. Furthermore, they demonstrate adaptability in adjusting to changes in their surroundings. Martínez-Monteagudo et al., conducted a study examining 1282 Spanish university students to understand the impact of social integration-related variables, such as support from friends and professors, on the likelihood of students experiencing academic abandonment. The research focused on students' adjustment to university life and explored the predictive nature of emotional issues (stress, anxiety, and depression) in relation to cyberbullying. The results revealed that high levels of melancholy increased the likelihood of becoming a cyberbully, while high stress levels increased the likelihood of being a victim of cyberbullying. Additionally, students with better social, emotional, and personal adjustment were less likely to fall prey to cyberbullying. The study emphasizes the importance of exploring the connection between the ability to adjust to college life and roles related to cyberbullying, whether as bullies or victims.

Table 6 outlines the affective self-esteem of students categorized as cyberbullies. Cyberbullies exhibit high self-esteem as they do not feel depressed when placed last (mean: 3.21, standard deviation: 0.58) and refrain from comparing themselves with others (mean: 3.64, standard deviation: 0.63). They demonstrate moderate self-esteem by handling criticism positively (mean: 2.93, standard deviation: 0.62) and not giving up when faced with challenges (mean: 2.93, standard deviation: 0.73). Additionally, they express moderate self-esteem by feeling happy when praised (mean: 3.21, standard deviation: 0.58) and being confident in expressing themselves (mean: 3.14, standard deviation: 0.66).

| Affective dimension |

Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

| Average and SD |

Interpretation |

Average and SD |

Interpretation |

| I am able to handle criticism positively. |

2.93 (0.62) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.03 (0.62) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I do not give up when something seems challenging. |

2.93 (0.73) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.06 (0.68) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I feel happy when someone praises me. |

3.21 (0.58) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.26 (0.74) |

High

self-esteem |

| When I place last, I do not feel depressed. |

3.29 (0.91) |

High self-esteem |

3.29 (0.83) |

High

self-esteem |

| I am confident to express myself. |

3.14 (0.66) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

2.91 (0.66) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I often see myself not comparing to others. |

3.64 (0.63) |

High

self-esteem |

3.6 (0.81) |

High

self-esteem |

| Note: 1.00-2.49: Low self-esteem, 2.50-3.24: Moderate self-esteem, 3.25-4.00: High self-esteem |

Table 6. Affective self-esteem of students according to their role as a cyberbully or a cybervictim.

On the other hand, the affective self-esteem of students categorized as cybervictims is presented. Cybervictims demonstrate high self-esteem, as they feel happy when praised (mean: 3.26, standard deviation: 0.74), do not feel depressed when placed last (mean: 3.29, standard deviation: 0.83), and avoid comparing themselves with others (mean: 3.6, standard deviation: 0.81). Additionally, they exhibit moderate self-esteem by handling criticism positively (mean: 3.03, standard deviation: 0.62), not giving up when faced with challenges (mean: 3.06, standard deviation: 0.68), and expressing confidence in themselves (mean: 2.91, standard deviation: 0.81).

The result highlights the significant link between emotion control and cyberbullying behaviors. Studies have established correlations between emotion control and aggressive actions, encompassing classic bullying. Cicchetti et al., found that both bullies and victims encounter challenges in emotion regulation techniques. While the relationship between emotion control and traditional bullying is well-explored, cyberbullying has received less attention. Notably, individuals involved in cyberbullying, whether as bullies, victims, or both, were found to struggle in articulating their feelings and experience more intense negative emotions compared to those not involved in bullying.

Furthermore, there is an observed increase in cyberbullying among teenagers lacking positive emotion control skills, such as cognitive reappraisal. Emotion control techniques significantly influence cyberbullying and cybervictimization behaviors. Long-term research indicates that adolescents employing non-adaptive emotion control techniques, such as rumination, self blame, other-blame, and catastrophizing, are more likely to engage in cyberbullying. In contrast, those utilizing adaptive techniques show a lower likelihood of participating in such behaviors. Additionally, cybervictims employing positive emotion regulation techniques, like perspective-taking, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, acceptance, and planning, demonstrate greater improvement than those utilizing negative techniques. It is anticipated that negative emotion regulation techniques, particularly expressive repression, may be associated with cyberbullying behaviors.

Table 7 outlines the academic self-esteem of students classified as cyberbullies. Cyberbullies demonstrate high self-esteem by maintaining hopefulness despite failing to achieve good performance in every activity (mean: 3.50, standard deviation: 0.76). They find inspiration when praised for improved grades (mean: 3.36, standard deviation: 0.63), feel motivated when efforts in school are appreciated (mean: 3.43, standard deviation: 0.65), and express comfort when comparing their academic performance with others (mean: 4.07, standard deviation: 0.73). However, they exhibit moderate self-esteem by being satisfied with their academic performance (mean: 2.79, standard deviation: 0.7) and not feeling upset when others perform better in school (mean: 2.93, standard deviation: 0.73).

| Academic dimension |

Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

Average

and SD |

Interpretation |

Average

and SD |

Interpretation |

| I am satisfied with my academic performance. |

2.79 (0.70) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

2.66 (0.68) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I still feel hopeful whenever I fail to achieve good performance in every activity. |

3.50 (0.76) |

High

self-esteem |

3.6 (0.74) |

High

self-esteem |

| I am inspired when someone praises me for getting better grades from my school performance. |

3.36 (0.63) |

High

self-esteem |

3.23 (0.69) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I do not feel upset when someone is doing good better than me in school. |

2.93 (0.73) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

2.91 (0.7) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I feel motivated when someone appreciates my effort in school. |

3.43 (0.65) |

High

self-esteem |

3.31 (0.72) |

High

self-esteem |

| I feel comfortable when they compare my academic performance with others. |

4.07 (0.73) |

High

self-esteem |

3.83 (0.86) |

High

self-esteem |

| Note: 1.00-2.49: Low self-esteem, 2.50-3.24: Moderate self-esteem, 3.25-4.00: High self-esteem |

Table 7. Academic self-esteem of students according to their role as a cyberbully or a cybervictim.

On the other hand, the academic self-esteem of students categorized as cybervictims. Cybervictims display high self-esteem as they remain hopeful even when failing to achieve good performance in activities (mean: 3.6, standard deviation: 0.74). They are motivated when their efforts in school are appreciated (mean: 3.31, standard deviation: 0.72) and feel comfortable when comparing their academic performance with others (mean: 3.83, standard deviation: 0.86). Additionally, they express moderate self-esteem by agreeing to be satisfied with their academic performance (mean: 2.66, standard deviation: 0.68), finding inspiration when praised for improved grades (mean: 3.23, standard deviation: 0.69), and not feeling upset when others perform better in school (mean: 2.91, standard deviation: 0.7).

The literature review on the relationship between cyberbullying and academic performance reveals inconclusive results. While many studies suggest a negative correlation between cyberbullying and academic achievement, others find no such correlation and highlight the greater impact of traditional social bullying on academic performance, as indicated by Torres et al. Overall, a thorough analysis of this relationship is crucial to emphasize the need for academic interventions for students involved in cyberbullying situations, whether as victims, bullies, or victimized bullies.

In terms of their academic performance, individuals are likely to display indicators such as low academic achievement, attention and focus issues, task failure, and a general lack of motivation or enthusiasm for learning. Consequently, several research projects have examined the importance of cognitive-motivational factors and academic adjustment in the development of cyberbullying and cybervictimization issues among young people.

Table 8 illustrates the family self-esteem of students categorized as cyberbullies. Cyberbullies exhibit high self-esteem by feeling happy when with their family (mean: 3.71, standard deviation: 0.47), experiencing joy when their families love them (mean: 4.29, standard deviation: 0.61), avoiding trouble easily at home (mean: 3.29, standard deviation: 0.61), feeling good about their family caring about their ideas (mean: 3.36, standard deviation: 0.63), and feeling sad when their family doesn't care about their ideas (mean: 4.14, standard deviation: 0.77). Additionally, they express moderate self-esteem by feeling that their families pay enough attention to them (mean: 3.21, standard deviation: 0.80).

| Family dimension |

Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

| Avg and SD |

Interpretation |

Avg and SD |

Interpretation |

| I feel happy whenever I'm with my family. |

3.71 (0.47) |

High

self-esteem |

3.46 (0.70) |

High

self-esteem |

| I feel happy whenever my family loves me. |

4.29 (0.61) |

High

self-esteem |

4.11 (0.72) |

High

self-esteem |

| My family pays enough attention to me. |

3.21 (0.80) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.11 (0.80) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I do not get in trouble easily at home. |

3.29 (0.61) |

High

self-esteem |

3.32 (0.87) |

High

self-esteem |

| I feel good about how much my family cares about my ideas. |

3.36 (0.63) |

High

self-esteem |

3.23 (0.73) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| It makes me good when my family didn’t care about my ideas. |

4.14 (0.77) |

High

self-esteem |

4.00 (0.84) |

High

self-esteem |

| Note: 1.00-2.49: Low self-esteem, 2.50-3.24: Moderate self-esteem, 3.25-4.00: High self-esteem |

Table 8. Family self-esteem of students according to their role as a cyberbully or a cybervictim.

Cybervictims, as depicted in Table 8, demonstrate family self-esteem. They express high self-esteem by feeling happy when with their family (mean: 3.46, standard deviation: 0.70), experiencing joy when their family loves them (mean: 4.11, standard deviation: 0.72), and feeling sadness when their family doesn't care about their ideas (mean: 4.00, standard deviation: 0.91). Additionally, they exhibit moderate self-esteem by feeling happy when their family pays enough attention to them (mean: 3.11, standard deviation: 0.80), avoiding trouble easily at home (mean: 3.20, standard deviation: 0.87), and feeling good about their family caring about their ideas (mean: 3.23, standard deviation: 0.73).

A German study involving 1987 teenage respondents found that 5.4% reported being victims of cyberbullying, with an additional 14.1% experiencing occasional cyberbullying. Notably, among 77 identified cyberbullies, 63 were also victims of cyberbullying at universities.

In contrast, a study by Triantoro S in 2015 revealed a significant difference in the level of family harmony among cyberbullying perpetrators and non-perpetrators. Cyberbullies engaging in the behavior several times demonstrated a higher level of family harmony, while those engaging only once or twice had a lower level of family harmony.

Furthermore, from the result we can see that individuals who were cyberbullied often refrained from reporting incidents to their families and law agencies due to concerns about being perceived as immoral and a lack of trust in these institutions. The treatment by families emerged as a significant stressor or consequence of cyberbullying encounters.

In table 9, the physical self-esteem of cyberbullies is highlighted. The findings reveal that cyberbullies exhibit high self-esteem by actively participating in physical exercise and wellness activities (mean: 3.50, standard deviation: 0.52). They also express confidence in their physical appearance (mean: 3.86, standard deviation: 0.77) and feel more confident and stronger when comfortable with their attire (mean: 3.36, standard deviation: 0.74). Moreover, cyberbullies derive happiness from compliments on their physical appearance (mean: 3.14, standard deviation: 0.66) and engage in positive self-talk related to their physical attributes (mean: 3.21, standard deviation: 0.58), indicating moderate self esteem. Interestingly, they also participate in physical activities due to a fear of judgment or failure, reflecting a moderate self-esteem (mean: 3.14, standard deviation: 0.95).

| Physical dimension |

Cyberbully |

Cybervictim |

| Avg and SD |

Interpretation |

Avg and SD |

Interpretation |

| I engage in physical exercise and activities that promote physical wellness. |

3.50 (0.52) |

High

self-esteem |

3.09 (0.85) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I feel confident of my physical appearance. |

3.86 (0.77) |

High

self-esteem |

3.91 (0.81) |

High

self-esteem |

| I receive compliments of my physical appearance. |

3.14 (0.66) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

2.97 (0.71) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| I engage in positive self-talk related to my physical attributes. |

3.21 (0.58) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

3.37 (0.77) |

High

self-esteem |

| I feel more confident and stronger when I’m comfortable with what I wear. |

3.36 (0.74) |

High

self-esteem |

3.46 (0.74) |

High

self-esteem |

| I engage in physical activities due to fear of judgement or failure. |

3.14 (0.95) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

2.94 (0.80) |

Moderate

self-esteem |

| Note: 1.00-2.49: Low self-esteem, 2.50-3.24: Moderate self-esteem, 3.25-4.00: High self-esteem |

Table 9. Physical self-esteem of students according to their role as a cyberbully or a cybervictim.

Cybervictims, as depicted in Table 9, showcase high self esteem by expressing confidence in their physical appearance (mean: 3.91, standard deviation: 0.82) and engaging in positive self-talk related to their physical attributes (mean: 3.37, standard deviation: 0.77). They also feel more confident and stronger when comfortable with their attire (mean: 3.46, standard deviation: 0.74). Moreover, cybervictims display moderate self-esteem by actively participating in physical exercise and wellness activities (mean: 3.09, standard deviation: 0.85). They derive happiness from receiving compliments on their physical appearance (mean: 2.97, standard deviation: 0.71) and engage in physical activities due to a fear of judgment or failure (mean: 2.94, standard deviation: 0.80), further illustrating moderate self-esteem.

Olweus and Limber challenge the findings, arguing that individuals who have been bullied may endure heightened anxiety or fear due to their distressing encounters with the bully. They contend that victims may lack effective coping mechanisms and may not know where to seek help. In their view, those who have experienced bullying may feel isolated and believe that others cannot comprehend the extent of their suffering.

Furthermore, they assert that bullied adults may face not only diminished self-esteem but also deteriorating physical well-being as a consequence of their traumatic experiences.

The surge in cyberbullying, characterized by its distinct features has underscored the need to explore the relationship between cybervictimization and body esteem, a crucial aspect of adolescent lives alongside the social framework, and potentially linked to cyberbullying victimization. In contrast, Shemesh DO and Heiman T dissent from this perspective, contending that cybervictimization significantly affects low body esteem, lack of social support, and low social self-efficacy. They assert that low social support and self-esteem heighten the vulnerability to becoming a cybervictim.

Table 10 shows the relationship between cyberbully encounter of both cybervictim and cyberbully to the level of self-esteem. The result presented is based on statistical analysis, likely regression or correlation, examining the relationship between different dimensions of self-esteem in cyberbullies and their encounters with cyberbullying. Here's a breakdown:

| Dimensions of self-esteem of cyberbully |

Cyberbullying encounters |

| R Stat |

P-value |

Decision |

Interpretation |

| Social dimension |

0.103 |

0.725 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Competence dimension |

-0.270 |

0.351 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Affective dimension |

0.460 |

0.098 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Academic dimension |

0.388 |

0.170 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Family dimension |

-0.121 |

0.680 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Physical dimension |

-0.188 |

0.521 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Overall self-esteem |

-0.008 |

0.978 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Note: Significant if p-value is ≤ 0.05, otherwise not significant. |

Table 10. Relationship between cyberbullying encounter to the level of self-esteem.

Social dimension: The R stat (correlation coefficient) is 0.103, and the p-value is 0.725. Since the p-value is greater than 0.05, it fails to reject the null hypothesis (Ho), indicating that there is no significant correlation between the social dimension of self-esteem and cyberbullying encounters.

Competence dimension: The R Stat is -0.270, and the p value is 0.351. Similar to the social dimension, there is no significant correlation between competence dimension and cyberbullying encounters.

Affective dimension: The R Stat is 0.460, and the p value is 0.098. Although the p-value is close to the significance threshold (0.05), it fails to reach it. Thus, there is no strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis, suggesting that the affective dimension is not significantly correlated with cyberbullying encounters.

Academic dimension: The R stat is 0.388, and the p value is 0.170. Similar to the affective dimension, the academic dimension is not significantly correlated with cyberbullying encounters.

Family dimension: The R Stat is -0.121, and the p-value is 0.680. No significant correlation is found between the family dimension of self-esteem and cyberbullying encounters.

Physical dimension: The R Stat is -0.188, and the p value is 0.521. Like other dimensions, the physical dimension is not significantly correlated with cyberbullying encounters.

Overall self-esteem: The R Stat is -0.008, and the p value is 0.978. There is no significant correlation between overall self-esteem and cyberbullying encounters. In summary, the statistical analysis fails to find significant correlations between various dimensions of self-esteem and cyberbullying encounters among cyberbullies. The "Not Significant" conclusion suggests that, based on the data, these dimensions of self-esteem do not have a clear and significant relationship with cyberbullying encounters.

The findings suggest that, based on the dimensions of self-esteem, there is no significant association with encountering cyberbullying, whether one is a cybervictim or a cyberbully. This lack of significance was surprising, particularly when considering the absence of notable differences in self-esteem levels among the four bully groups.

It's noteworthy that those who did not engage in cyberbullying exhibited self-esteem levels comparable to those categorized as cybervictims or bullies. However, a closer examination of the overall self-esteem scores in the sample indicated that all four groups reported levels of self-esteem considered average for young adults, as per Sinclair et al.

Furthermore, the study revealed that very few participants reported high rates of cybervictimization or cyberbullying, with the majority of bullies and victims falling into the category of light engagement. A minority reported significantly higher levels of cyberbullying and victimization.

From these results, it can be inferred that mild or occasional cyberbullying might not have the same profound effects on fluctuations in self-esteem among young adults as more severe cases of cyberbullying. The implication is that the intensity or frequency of cyberbullying may play a role in its impact on self esteem in this demographic (Table 11).

| Dimensions of self-esteem of cybervictim |

Cybervictim encounters |

| R Stat |

P-value |

Decision |

Interpretation |

| Social dimension |

-0.102 |

0.559 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Competence dimension |

-0.099 |

0.573 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Affective dimension |

-0.330 |

0.053 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Academic dimension |

-0.025 |

0.886 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Family dimension |

0.024 |

0.889 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Physical dimension |

0.047 |

0.789 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Overall self-esteem |

-0.157 |

0.369 |

Failed to reject Ho |

Not significant |

| Note: Significant if p-value is ≤ 0.05, otherwise, not significant. |

Table 11. The relationship between cyberbullying encounter to the level of self-esteem of cybervictim.

Conclusion

The results indicate that, for cybervictims, there is no significant association between the dimensions of self esteem and their encounters with cybervictimization. The p-values for all dimensions, including social, competence, affective, academic, family, and physical, are above the threshold of 0.05, suggesting that the null Hypothesis (Ho) is not rejected for each dimension. In other words, there is no statistically significant difference in the self-esteem dimensions between those who have experienced cybervictimization and those who have not, based on the chosen dimensions of self-esteem. The lack of significance implies that cybervictimization, as measured in this study, does not appear to have a significant impact on the various aspects of self-esteem in the studied sample.

The results suggest that there is no substantial correlation between experiences of cybervictimization or cyberbullying and various aspects of self-esteem. This means that the encounters with online victimization or perpetration, as measured in the study, do not significantly impact the different dimensions of self esteem.

The study anticipated that the cyberbully/victim group would show stronger characteristics of both bullying and victimization compared to distinct cyberbully and cybervictim groups. The results confirmed this expectation, as the cyberbully/victim group reported the highest scores in both bullying and victimization. This suggests that individuals in this group might be more prone to participating in the cycle of bullying. The implication is that the cyberbully/victim group possesses additional traits that heighten their likelihood of engaging in bullying behavior and becoming targets, potentially influenced by factors such as friendship networks and empathy.

References

- Abaido GM. Cyberbullying on social media platforms among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2020;25(1):407-420.

[Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi S. Academic Self-Esteem, Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Achievement: A Path Analysis. J Foren Psy. 2020;5(1):1–6.

- Aliyev R, Gengec H. The effects of resilience and cyberbullying on self-esteem. J Educ. 2019;199(3):155-165.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Touloupis T. Facebook use and cyberbullying by students with learning disabilities: The role of self-esteem and loneliness. Psychol Rep. 2024;127(3):1237-1270.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Batican ED. Development of Multidimensional Self-Concept Scale (mSCS) for Filipino college students. ADDU-SAS Grad Res J. 2011;8(1):1-15.

- Lozano-Blasco R, Cortes-Pascual A, Latorre-Martínez MP. Being a cybervictim and a cyberbully–The duality of cyberbullying: A meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;111:106444.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Brack K, Caltabiano N. Cyberbullying and self-esteem in Australian adults. Cyberpsychol J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace. 2014;8(2).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G, Kerslake J. Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;48:255-260.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Bachmann L. Perpetration and victimization in offline and cyber contexts: A variable and person oriented examination of associations and differences regarding domain-specific self-esteem and school adjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10429.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cenat JM, Hebert M, Blais M, Lavoie F, Guerrier M, Derivois D. Cyberbullying, psychological distress and self-esteem among youth in Quebec schools. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:7-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi B, Park S. Who becomes a bullying perpetrator after the experience of bullying victimization? The moderating role of self-esteem. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(11):2414-2423.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi B, Park S. Bullying perpetration, victimization, and low self-esteem: Examining their relationship over time. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(4):739-752.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chu XW, Fan CY, Liu QQ, Zhou ZK. Stability and change of bullying roles in the traditional and virtual contexts: A three-wave longitudinal study in Chinese early adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47:2384-2400.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crocker J, Luhtanen RK. Level of self-esteem and contingencies of self-worth: Unique effects on academic, social, and financial problems in college students. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(6):701-712.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Extremera N, Quintana-Orts C, Merida-Lopez S, Rey L. Cyberbullying victimization, self-esteem and suicidal ideation in adolescence: Does emotional intelligence play a buffering role?. Front Psychol. 2018;9:367.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garaigordobil M, Navarro R. Parenting styles and self-esteem in adolescent cybervictims and cyberaggressors: Self-esteem as a mediator variable. Children. 2022;9(12):1795.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harris MA, Orth U. The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2020;119(6):1459.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hosogi M, Okada A, Fujii C, Noguchi K, Watanabe K. Importance and usefulness of evaluating self-esteem in children. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012;6:1-6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Juvonen J, Graham S. Bullying in schools: The power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65(1):159-185.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mishna F, Khoury-Kassabri M, Gadalla T, Daciuk J. Risk factors for involvement in cyber bullying: Victims, bullies and bully–victims. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34(1):63-70.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

Citation: Effect of Cyberbullying on Facebook to the Self-Esteem of Students ASEAN Journal of Psychitary Vol. 26 (1) February,

2025; 1-13