Introduction

Hospital Mesra Bukit Padang is one of four

mental institutions under the Malaysian Ministry

of Health (MMH). Each covering multiple states,

the facilities are tasked to treat the mentally ill,

both civil and forensic. It is common to have

long stay chronic wards in mental institutions

and aside from the one reserved for Criminal

Procedure Code (CPC) section 348 (patients

ordered by the civil court to be held in ward),

there are several chronic wards in HMBP (male

and female) [1].

Throughout the years, it was found that the

number of psychiatric patients is increasing,

along with inpatient admission as well. After

completing their acute treatment in HMBP, the

doctors found difficulties to discharge these

patients back to their home [2]. Most of them,

with their mental health stabilized, found to have

social issues which the clinicians and allied

health units have difficulty resolving. There were

not many options available during discussions:

To continue trying to contact and negotiate with

the families or continue keeping these patients by transferring them to chronic wards. As

establishing our center to be a center of

excellence is our vision and hoping to improve

the mental health services, a solution must be

found in reducing mental institutionalization in

Sabah.

Materials and Methods

Mental institutions are tasked to treat the

mentally ill and to house those who are deemed

unable to return to the normal society. After

United Nation and WHO declare the policies of

deinstitutionalization (WHO: The World Health

Report 2001), multiple studies have mentioned

about the rationale of the implementation. The

main struggle has always been the economic

burden of institutionalization [3].

With the prevalence of mental illness increases,

without the community’s support, hospital Mesra

have faced issues of full occupancy, which leads

to the same financial difficulties as mentioned

earlier, staggering the quality of care provided to

the patients [4].

Knapp, et al. has reported in 2011 that the effort

of de-institutionalization must be done right with

the cooperation of multiple agencies. By having

a well-developed system in the community

setting, the overall cost of treatment can be

vastly reduced. Otherwise, it would just be the

same as diverting the cost to other organizations.

In this study we hope to address the issue of high

Bed Occupancy Rate (BOR) in HMBP. We

gather data of the common reasons for patient

admission to chronic wards and find which ones

are associated to patient having difficulty to be

discharged home. Among those reasons, we

would also be looking at the illness perspective,

whereby does the severity of their illness play a

role? With that information, we hope to develop

a solution to the issue [5].

To assess the severity of a psychiatric illness, we

chose the Brief Psychiatry Rating Scale (BPRS)

version 4.0 as it is a validated widely used

clinician rated assessment tool with good validity

and reliability.

The BPRS is a widely used measurement

instrument to assess the changes in severity in

psychopathology in a wide variety of severe

psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia,

depression and bipolar disorders which are found

to be common diagnoses in the chronic wards.

The BPRS version 4.0 includes an expanded twenty-four items, which also cover the observed

behavior and appearance assessment during

interview [6].

Objective

The aim of the audit is to look for ways to reduce

BOR of chronic wards. At the same time, we

wish to identify the common reasons of long

inpatient stay in wards in HMBP so that we can

strategize our approach more effectively.

Any recommendation would be based on

standards of care compliance to:

• Psychiatric and mental health services

operational policy (Nov 2011), Ministry

of Health Malaysia (MHM): Section 6.2,

inpatient services and section 6.4

hospital based community psychiatry.

• Mental health act 2001 and mental

health regulation 2010.

• Mentari MOH implementation guideline

2nd edition 2020.

A team of auditors carried out a retrospective

audit looking at numbers and reasons of all

inpatients that are staying longer than 3 months

in hospital Mesra Bukit Padang by the time of

the audit. All patients who are admitted for more

than 3 months are included in the study, while

excluding those who are detained under the court

order CPC section 342, 344 and 348.

Results and Discussion

Data collection was by a team of medical

officers by looking through patients’ clinical

notes, administering a rating scale and filling up

a data collection form. Relevant data to be

collected are:

• Basic demographic information

• Total length of stay in ward

• Medical conditions: Underlying

illnesses

• Psychiatric condition

• Dependency of Activities in Daily

Living (ADL)

• Reasons of keeping patient in ward:

Medical/Psychiatric/Social

• Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

Additional data of Bed Occupancy Rate (BOR)

and Average Length of Stay (ALOS) of chronic

wards (Ward 4, 5, 9 and 10) are collected by

looking back at the ward census.

This study's data collection period lasted

from May 15, 2023, to June 30, 2023.

The sociodemographic data was analyzed and

described using descriptive statistics such as

frequency, percentage, mean and standard

deviation using IBM SPSS version 28.0. To

facilitate analysis, categorical variables were

transformed into dummy variables. The variables

are checked for normal distribution. Associations

between the variables are analyzed by using Man-Whitney-U test and correlations between

numerical data are analyzed using linear

regression model.

A total of 60 patients are recruited in this study

by sampling all patients that fit the criteria in all

chronic wards. Relevant data are extracted from

their clinical notes and their psychiatric

conditions are assessed by administering BPRS

cross sectionally shown in Table 1. The findings

are tabulated as below:

| Variables |

N=60 |

Mean (sd) |

P-value |

| Yes (%) |

No (%) |

| Length of stay in ward (days) |

2078.50 (5281)* |

|

| Age (years) |

55.06 (12.17) |

| Number of comorbidities |

2 (2)* |

0.209a |

| ADL dependent |

2 (3.3) |

54 (90.0) |

- |

0.657a |

| Primary diagnosis |

0.649a |

| Schizophrenia |

55 (91.7) |

5 (8.3) |

- |

|

| Dementia |

3 (5.0) |

57 (95.0) |

- |

|

| Major depressive disorder |

1 (1.7) |

59 (98.3) |

- |

|

| Schizoaffective disorder |

1 (1.7) |

59 (98.3) |

- |

|

|

Reasons of keeping patients

|

| Medical illness requiring inpatient care |

2 (3.3) |

58 (96.7) |

- |

|

| Maintenance ECT |

6 (10.0) |

54 (90.0) |

- |

|

| Psychiatrically unstable |

9 (15.0) |

51 (85.0) |

- |

|

| Optimization of psychotropic (Clozapine) |

3 (5.0) |

57 (95.0) |

- |

|

| Family uncontactable |

21 (35.0) |

39 (65.0) |

- |

|

| Family refuse to take patient |

24 (40.0) |

36 (60.0) |

- |

|

| Awaiting nursing home |

6 (10.0) |

54 (90.0) |

- |

|

| Other social issues |

8 (13.3) |

52 (86.7) |

- |

|

| BPRS score |

|

|

27.10(3.48) |

|

Note: *Median (IQR), aMan-Whitney-U test, bSpearman’s correlation’s regression model

Table 1. Relevant data are extracted from their clinical notes.

We use the length of stay in ward as an outcome

variable. Schizophrenia is the most common

diagnosis among chronic inpatients (91.7%).

Social reasons are the highest frequency: Family

refuses to take patient (40%), family

uncontactable (35%), awaiting nursing home

(10%) and other social issues (13.3%). There is

noted significant association between

maintenance ECT and length of stay in ward (P

value=0.022). Thus, we can say that the

treatment of maintenance ECT is associated with

longer patient stay in the ward. There is slight

significance noted between family uncontactable

and length of stay in ward (P value=0.049).

There is an association between family uncontactable and increment of length of stay in

ward [7].

There is no association between reasons of

primary diagnosis, medical illness requiring

inpatient’s care, psychiatrically unstable,

optimization of psychotropic (Clozapine), family

refuse to take patient, awaiting nursing home,

other social issues and the length of stay in ward.

There is no correlation between the length of

stay in ward with patients’ BPRS score,

(Spearman’s ρ=0.004, P=0.487). So, there is no

association between patient’s severity of illness

and length of stay in ward (Table 2, Figures 1

and 2). The admission data in chronic wards are

as follows:

| Year |

Gender |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Ward 4 |

M |

93.54 |

95.11 |

86.11 |

97.54 |

83.88 |

| Ward 5 |

F |

83.42 |

87.62 |

57.11 |

44.84 |

52.08 |

| Ward 9 |

F |

54.63 |

68.09 |

81.59 |

87.78 |

84.93 |

| Ward 10 |

M |

84.61 |

86.34 |

74.4 |

85.68 |

89.14 |

| Ward 8 |

M |

68.3 |

74.58 |

51.81 |

65.29 |

69.69 |

Table 2. Bed Occupancy Rate (BOR) of chronic wards in HMBP (%).

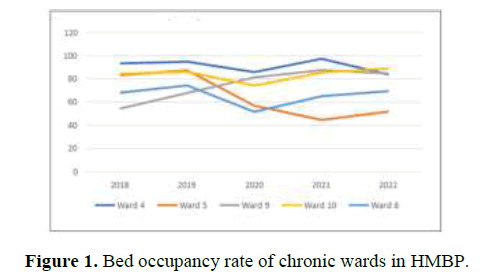

The BOR of chronic words is as shown above. It

shows that aside from ward 5, all other wards are

static in numbers of patients in ward. Do note

that there is a movement of patients between

ward 8, ward 5 and ward 9 due to the conversion

of roles of wards between them in year 2020.

That may contribute to the changes. Ward 9, 10

and 5 have the highest BOR, which on average

84% for Ward 9 and 10 and 91% for ward 5.

(Ward 9 serves as chronic female ward since

2020, the average BOR for past 3 years is 84%)

[8,9].

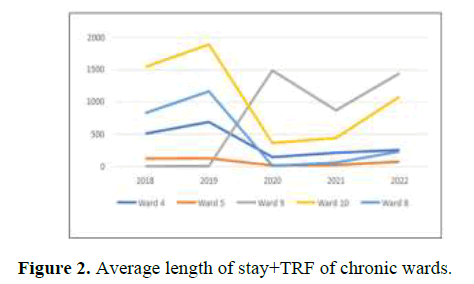

The Average Length of Stay (ALOS) of patients

in chronic wards shows a steady climb across the

graph for the past 3 years. The steep changes in

2019 may be due to the movement of patients

between wards as the ward switch their roles.

The high ALOS in ward 9 and 10 is expected as

those are female and male chronic wards for the

elderly, which most their patients are of

exceptionally long stay and difficult to discharge

(Table 3).

| Year |

Gender |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| Ward 4 |

M |

512.15 |

694.27 |

152.08 |

217.98 |

262.43 |

| Ward 5 |

F |

130.49 |

133.25 |

22.57 |

30.31 |

82.37 |

| Ward 9 |

F |

11.94 |

12.55 |

1489 |

873.82 |

1446.67 |

| Ward 10 |

M |

1544.17 |

1890.8 |

370.32 |

446.76 |

1084.56 |

| Ward 8 |

M |

831 |

1166.71 |

16.59* |

67.44* |

238.47* |

Table 3: Bed Occupancy Rate (BOR) of chronic wards in HMBP (%).

The association of maintenance ECT and length

of stay in ward is evident, as maintenance ECT

requires patient to come to HMBP as frequent as

weekly for the treatment and there are no

hospitals within the cluster to offer such service

yet. Such treatment frequency brings expected

logistic issues, especially for those who live far

away in other cities. There is a need for more

centers offering this service to bring it closer to

the people. However, before such step even

become feasible, more psychiatry units need to

be established first, which will require resources

in all forms [10].

The reason of ‘family uncontactable’ being

associated with length of stay in ward can be

justified by the non-existence of any social

support available for these patients. Different

than those of ‘family refused to take patient’ who

still has family member around for the hospital

staffs to engage with, these patients have no one

for the hospital staffs to contact with. There is

also no agency that would provide

accommodation for them because of the lack of a

legal confidant. Thus, the increment of their

length of stay in ward is almost inevitable [11].

One issue worth highlighting is that there is no

association noted between the severity of illness (BPRS score) and the length of stay. This

supports the notion that severity of their

psychiatric illness has no influence on their

length of stay in ward. Some patients in chronic

wards are psychiatrically stable but stay longer

than others. This is not cost effective as there are

better ways to help such patients to be

independent in the community, while conserving

our hospital resources for those who need it

more. Such strategies will be discussed below.

Social reasons are the most common reason for

patients unable to be discharged from HMBP.

The data shows a discrepancy in between the

reasons frequency (%) and their significance of

association (P-value). Such discrepancy suggests

that there are more patients with reasons that

without significance are being kept longer in

chronic ward. Urgency is needed to address this

issue due to the impact it can have on our

psychiatry service, such as budgeting, facility

usage and service quality. Although it is a

common issue found in all mental institutions in

Malaysia, it is worth reminding ourselves that it

is a preventable matter [12].

The reluctancy of family members to bring the

patients home suggests stigmatization. The lack

of understanding and stigma from family members are main contributing factors for them

to become reluctant to care for their loved ones

at home. The effort to engage with the families

has been done with the help of social workers, by

repeating phone calls and family tracing but

there is no improvement in the BOR [13].

Although addressing stigmatization objectively

will require another research, the authors hope to

include this topic in discussion to look for

possible countermeasures for this serious

phenomenon. Another issue of concern is the

costs of in-patient care. Based on monthly report

by finance unit, for April 2023, HMBP has

recorded total admission of 4582 patient days.

For the cost of inpatient treatment alone, HMBP

spends a total of RM 2.7 million in just a month.

This number, when compared to outpatient costs,

which is RM 280,000 for 1,660 patients in April

2023, an almost difference of 10 fold is observed

[14]. Considering that there are patients who are

psychiatrically stable, who do not require active

psychiatric intervention and just for continuation

of medication, such costs of inpatient care may

not be cost effective in the service.

Recommendation

There is always a concern of patients being

unwell when they are discharged without a

caretaker. So, mental institutions adopted the

concept of having chronic wards for

rehabilitation purpose. With the increment of

needs for accommodating the mentally ill who

are having social difficulties, much effort has

done to expand the infrastructure as we seen in

other centers such as hospital Permai and

Bahagia. The option of expansion of chronic

wards is although doable, but not cost effective.

By allowing more psychiatric patients to stay in

ward, it requires more budgets to sustain their

inpatient care, be it resources of workforce,

medical equipment and daily needs like food and

utilities. With the expansion of available services

and subspecialties, the national budget should be

well spent on enhancing the quality of care

towards our patients.

Many countries, including WHO, have proposed

the idea of de-institutionalization since more

than 50 years ago. However, there are mixed

reports regarding its outcome, as each report

offers different perspectives: clinical,

socioeconomical and ethical points of view.

However, it consistently shows that with a good

well planned community strategy, much benefit

can be gained even from the socioeconomical point of view (Knapp, et al., 2010). Based on a

systemic review by McPherson et al in 2018,

there is a noted benefits in supported

accommodation that it improved appropriate use

of service and reduction in hospitalization among

de-institutionalized patients. Thus, we propose a

program of supported accommodation, with

Hospital Permai Johor Bahru as a reference

point.

Hospital Permai has implemented supported

accommodation for patients who are deemed

psychiatrically stable and fit to live by

themselves. As compared to the inpatient chronic

residency, which consist of having patients under

hospital care staying inside an apartment built

within hospital grounds, supported

accommodation involves patient living in

accommodation units outside the hospital, which

premises mostly are given by local authorities

who support the program. Patients are required

to work, often by supported employment, to pay

for their rent (amount about RM70) and daily

expenses. The community psychiatry team

would visit them regularly to check on their

progress and support the local communities by

giving out education in order to help to reduce

stigma towards the patient. So far, as when this

report is written, seventeen patients in HPJB

chronic wards were successfully gone through

the program, sustaining themselves with a job

within the community. One strategy currently

underway is to transfer chronic patients who

require constant medical care and psychiatrically

stable to the district hospital as lodgers. This is

done out of the need of bed vacancy and it is not

cost effective as other hospitals too will share the

cost burden.

Another strategy is to lower the admission rates

altogether, by improving our service. A stronger

therapeutic alliance is needed between clinician

and the family members. Psychoeducation is

important in reducing stigmatization. Study has

shown that it improvesthe long-term outcome

among patients of schizophrenia, by having a

reduction of relapse rate of 50-60% (McFarlane,

2016). We suggest implementing a structured

psychoeducation module for the patients and

family. The Ministry of health provided a

structured psychoeducation module for family

and patients, which comprises 8 components.

However, there is a constant need for resources

to have the facility and staff to routinely

administer such modules effectively. There is a

need to establish more treatment centers available within the area. Treatment gap refers to

the difference between those who require

treatment and those who got treated. In

psychiatry, is has known to be a worldwide issue

as there are huge difficulty for the mentally ill to

get the help they need. Such difficulty will bring

delay in treatment, resulting in adverse outcome.

With a wide area of coverage handled by HMBP,

it receives psychiatry patients with the need of

admission from areas from Beaufort all the way

to Kudat (Distance of 400 km). Out of the

cluster’s hospitals, there’s only HMBP who are

equipped with psychiatry ward at the moment of

this report. So, much urgency is needed to have

other centers within the cluster to be equipped

with psychiatry units, to reduce the patient load

in HMBP.

Approaches like community outreach are also

important in reducing the need for psychiatric

admission. A recent study done in Kuala Lumpur

has shown that a good outreach strategy could

reduce patient readmission rate. Community

outreach encompasses mental health promotion

to the public, educating primary caregivers,

preparing the public health sector the skills

needed to identify the illnesses, as well as

working with different agencies to provide

support to those who are affected. Such an

approach has been implemented in HMBP,

which is having a community mental health

center focusing on rehabilitation called

‘Mentari.’ Mentari program has been

implemented in the national practice since The

Eleventh Malaysia Plan (EMP-2016-2020). The

aim is to have a community center that focuses

on rehabilitation of the mentally ill and reduce

the illness burden, by giving out supported

employment, psychosocial rehabilitation,

sheltered workshop, home visit and social

enterprise. It is also focused on reducing stigma

within the community. However, as of now, only

one Mentari center is available on the west coast

of Sabah and it is stationed within HMBP

ground. The team urges the need to establish

more community mental health centers.

Good alliances with other agencies are important

as well. There is a need to clarify that with deinstitutionalization,

the economic burden for

patients with great disability will be shared

between agencies such as healthcare, social

welfare, as well as families. So, there must be a

good collaboration between agencies to achieve

cost effectiveness. Hospital social welfare that

are engaging with the family members are facing

difficulty due to lacking resources. The options presented for them are limited, as financial aid

and supported accommodations options are

scarce and nursing homes are mostly run by the

private sectors or NGO, thus incurring a demand

in price to the families. We suggest a frequent

discussion with the state social welfare and

NGOs to discuss a means of collaboration to

maximize each other’s role in service.

Conclusion

• Social factors are the most common

reason for chronic inpatient stay in

HMBP.

• Severity of psychiatric illness is not

associated with the length of stay of

chronic inpatients.

• Cost efficiency demands steps to be

taken to reduce the inpatient load, such

as: Implementation of psychoeducation

module; establishing new Mentari

centers and outreach strategies.

• Supported accommodation.

Limitations

The author acknowledges that assessment

towards the caregiver’s perspective such as

their stigmatization would provide a more

concrete data, but there’s a difficulty in

engaging family members of patients in chronic

wards as they are usually difficult to meet with

clinicians. There might exist an inter rater

variability when administering BPRS by

different clinicians. A brief meeting and

teaching have been conducted between the

clinicians and they are instructed to comply

with the BPRS manual. The recommendations

are for reference purposes for the hospital

administrators as the author is not stationed on

site.

Acknowledgment

The Authors would like to thank Hospital

Mesra Bukit Padang for allowing the audit to

be taken place and the cooperation from the

admin and staff during the audit period.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of

interest regarding the publication of this article.

This research did not receive any specific grant

from funding agencies in the public,

commercial or not-for- profit sectors. This audit

receives no funding or sponsors from any party.

Ethical Issues

The project is pending approval from the

Malaysia Research Ethical Committee (MREC)

approval.

References

- Chow WS, Priebe S. Understanding psychiatric institutionalization: A conceptual review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):1-4.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shen GC, Snowden LR. Institutionalization of deinstitutionalization: A cross-national analysis of mental health system reform. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014;8(6):1-23.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McDaid D, Knapp M, Raja S. Barriers in the mind: Promoting an economic case for mental health in low-and middle-income countries. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):79-86.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raaj S, Navanathan S, Tharmaselan M, Lally J. Mental disorders in Malaysia: An increase in lifetime prevalence. B J Psych International. 2021;18(4):25-30.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hofmann AB, Schmid HM, Jabat M, Brackmann N, Noboa V, et al. Utility and validity of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) as a transdiagnostic scale. Psychiatry Research. 2022;314(143):614-659.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10(3):799-812.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer A. Meta-analysis of the brief psychiatric rating scale factor structure. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17(3):324.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, Liberman RP. Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale:" the drift busters." International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;11(8):77-83.

[Google Scholar]

- Monnapula-Mazabane P, Petersen I. Mental health stigma experiences among caregivers and service users in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. Current Psychology. 2023;42(11):9427-9439.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McPherson P, Krotofil J, Killaspy H. Mental health supported accommodation services: A systematic review of mental health and psychosocial outcomes. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(6):1-5.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knapp M, Beecham J, McDaid D, Matosevic T, Smith M. The economic consequences of deinstitutionalization of mental health services: lessons from a systematic review of European experience. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2011;19(5):113-125.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McFarlane WR. Family interventions for schizophrenia and the psychoses: A review. Family Process. 2016;55(24):460-482.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dahlan R, Midin M, Sidi H, Maniam T. Hospital-based community psychiatric service for patients with schizophrenia in K uala L umpur: A 1 year follow up study of re-hospitalization. Asia Pacific Psychiatry. 2013;5(2):127-133.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fekadu A, Medhin G, Lund C, DeSilva M, Selamu M, et al. The psychosis treatment gap and its consequences in rural Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(8):1-11.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Clinical Audit Report: Number, Reasons and Indication of Inpatient in Chronic Wards in Hospital Mesra Bukit Padang, Sabah, Malaysia. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 25 (1) January, 2024; 1-8.